Nostos

(Ancient Greek: νόστος) is a theme used in Ancient Greek literature, which includes an epic hero returning home by sea. In Ancient Greek society, it was deemed a high level of heroism or greatness for those who managed to return. This journey is usually very extensive and includes being shipwrecked in an unknown location and going through certain trials that test the hero.[1] The return is not only about returning home physically, but also focuses on the hero retaining or elevating their identity upon arrival.[2]

When I left Japan for the United States at twenty-four, nearly fifteen years ago, I didn’t give much thought to what it meant to be Japanese. My heritage—my identity—was something I took for granted. This is easy to do when you come from a country such a Japan which I like to describe as a monoculture. Growing up, all my friends, all my family, everyone around me was one-hundred percent Japanese, with no ethnic or religious variety. Conformity to rules and tradition was considered a given. At my mother’s direction, my childhood was filled with traditional ceremonies of Japanese life—Hinamatsuri, Obon, Oshogatsu, celebrating Girls Day, Ones Ancestors, and Japanese New Year. But I never paid attention to these. In fact, I disregarded them as further symbols of the staid formality of Japanese culture, which is steeped in too many programmatic customs to allow room for the originality I craved even from a young age.

You see, growing up, I didn’t simply feel different from the people—the entire culture and nation—who surrounded me, I was different. I was born with little pigment in my skin and hair. I was more emotional than my friends and family. I craved new challenges instead of the repetitive tasks we were assigned at school. I was also born left-handed – and wrote my notes in mirror script, which was natural to me.

In a country such as America, where there is not one way to appear American either physically, culturally, or spiritually—where difference can be celebrated instead of repressed and reviled—it’s hard to understand how shameful these superficial differences were to me and my family. As I grew up, I felt a tremendous amount of guilt that my parents were saddled with such a strange, unfortunate kid as myself.

I’m not sure if it was because of my appearance and weirdness, but I knew from the start that I was not going to be able to conform to the culture around me, nor would I want to. Even as a child, I was creative and ambitious. My passion for creating art and turning it in to a business was considered vulgar by most Japanese people, especially in the small town where I grew up. (Talking about and desiring even modest amounts of money and success is simply not acceptable in our culture.) My drive to be creative and for that creativity to provide economic support, caused me to turn my back on the conventions, rules, and traditions of my heritage. After studying Philosophy at Kobe College, one of the most Westernized colleges in Japan, I left for the United States where I studied graphic design at FIDM and later painting and sculpture at the Art Center College of Design.

In California, I was surprised by Americans’ curiosity about Japanese culture, not to mention their continual misinterpretation of it and the ease with which they appropriate it for their own purposes. For the first time in my life, people began asking me about what it meant to be Japanese—something I had given little thought to before leaving home. I had to begin to consider myself and my culture carefully—I had to look at who I am from an outsider’s perspective and really think about how that matched up with how I felt deep within myself.

This process, which is ongoing, was made harder by the fact that all around me in Los Angeles (and elsewhere in America and the rest of the world) I am confronted with misappropriations of Japanese culture. The signs of this are everywhere and make me wonder what it means to be Japanese in a place that imagines sushi and ramen and coexist in the same restaurant and neighborhoods such as Little Toyko and Japantown are authentic replicas instead of closer to something imagined by the creators of Disneyland.

I cannot stand influential people who believe they represent Japanese culture while ambiguously nodding to aspects of Japan with misplaced confidence. It makes me sad, and a little bit angry, when respected people do this for attention and capital gain. Now, don’t mean people who take ideas from Japanese culture or traditions. As an artist and a creator, I, too, borrow ideas from everywhere. It’s part of the process of making new things. But the point is to adapt what you find in another culture to your world view, not simple to offer it for sale as your own. There are too many designers who feel comfortable representing traditional Japanese things in their shops. These are people who went to Japan once or twice and were so impressed that they started selling Japanese objects—literal objects used in our sacred ceremonies without adapting them or changing them or even understanding them.

At the same time that I was being asked to define and explain my heritage, I was being flooded with incorrect information about it—signs and labels that distorted the traditions with which I grew up. I had run from Japan in an attempt to become more Westernized, but in doing so, I was being, for the first time, forced to define myself as Japanese, while all around me were incorrect interpretations of what that meant.

I began to think about how easily and often people borrow from Japanese culture and why we as Japanese don’t fight back against it. (I am well aware of how fraught the subject of cultural appropriation is these days, so I find this especially curious. Why is my culture up for grabs while people have been cautioned about borrowing African, African-American, and Chinese symbols and signifiers?)

I can only speak for myself when I explain why it doesn’t brother when I see a fellow designer produce something that is clearly deeply inspired by Japan—whether a kimono dress, samurai pants, or a traditional zori sandals. My first instinct upon seeing these things is to give the designer the benefit of the doubt that he or she knows or understands Japanese culture. And my second thought is usually to dismiss all questions of authenticity as irrelevant because I can see that these designs are simply false copies and not Japanese and therefore of little consequence to me as a person or a designer.

Yet I worry that my attitude is too careless. Shouldn’t it bother me that people feel confident stealing from my heritage without knowing anything about it? Shouldn’t I want to be more protective of my native traditions? Shouldn’t it make me uncomfortable that the very culture I worked hard to leave behind is being falsely celebrated and diluted all around me? Shouldn’t I stop to wonder how it is that the things I fled from as a designer are at the disposal of people who know little or nothing about Japan?

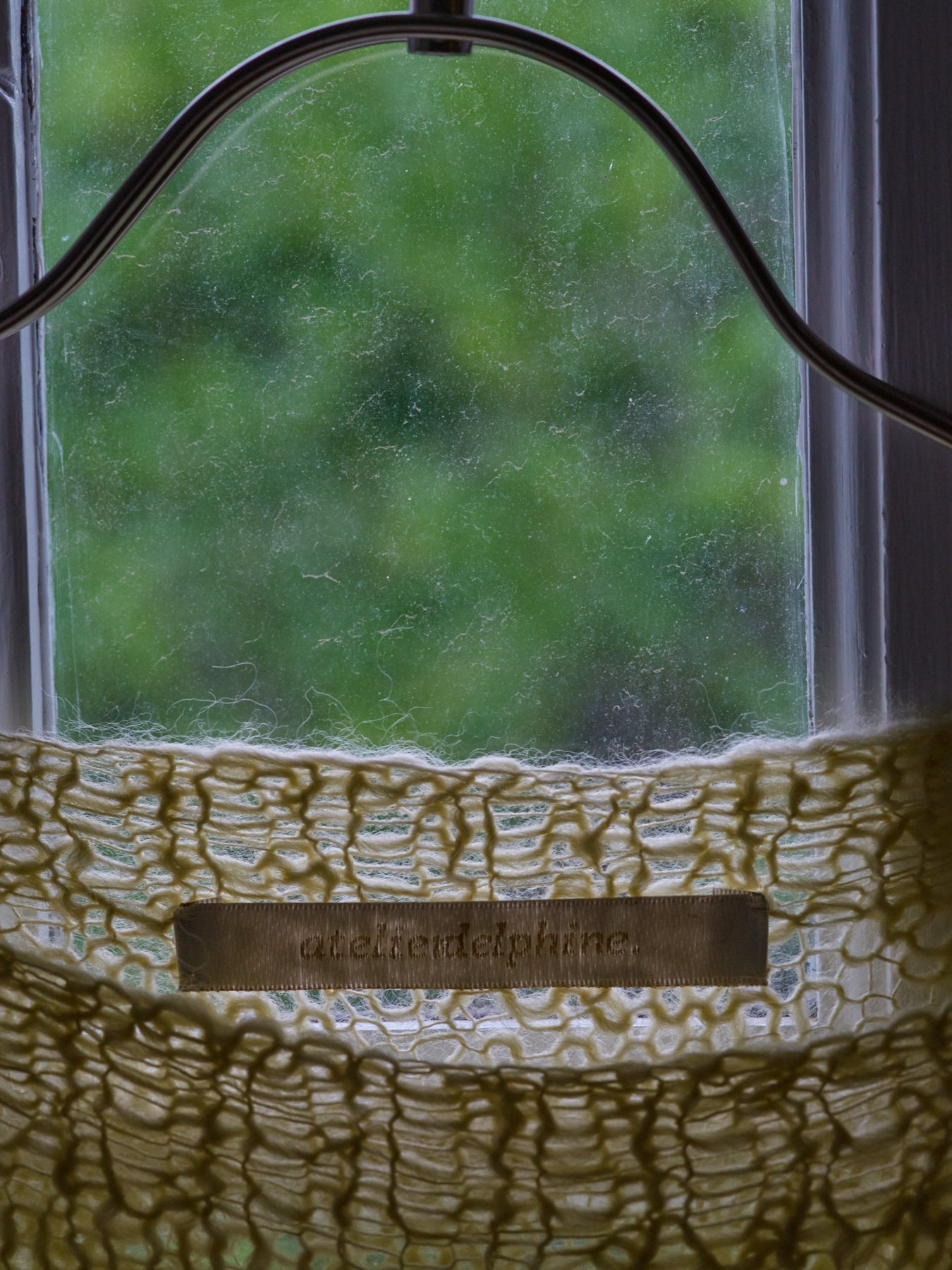

It’s strange how sometimes the thing you imagine you need to escape returns to you unexpectedly. When I started my company, Atelier Delphine named after Catherine Deneuve’s character in Friends from Rochefort—you see, my own cultural appropriation at play here—I did it because I was trying to put as much distance between myself and my Japanese upbringing as I could. But slowly elements of Japanese culture started to appear in my clothing. Having not paid attention to the countless traditional ceremonies my mother insisted upon in my youth, I hadn’t realized how deeply affected I was by these.

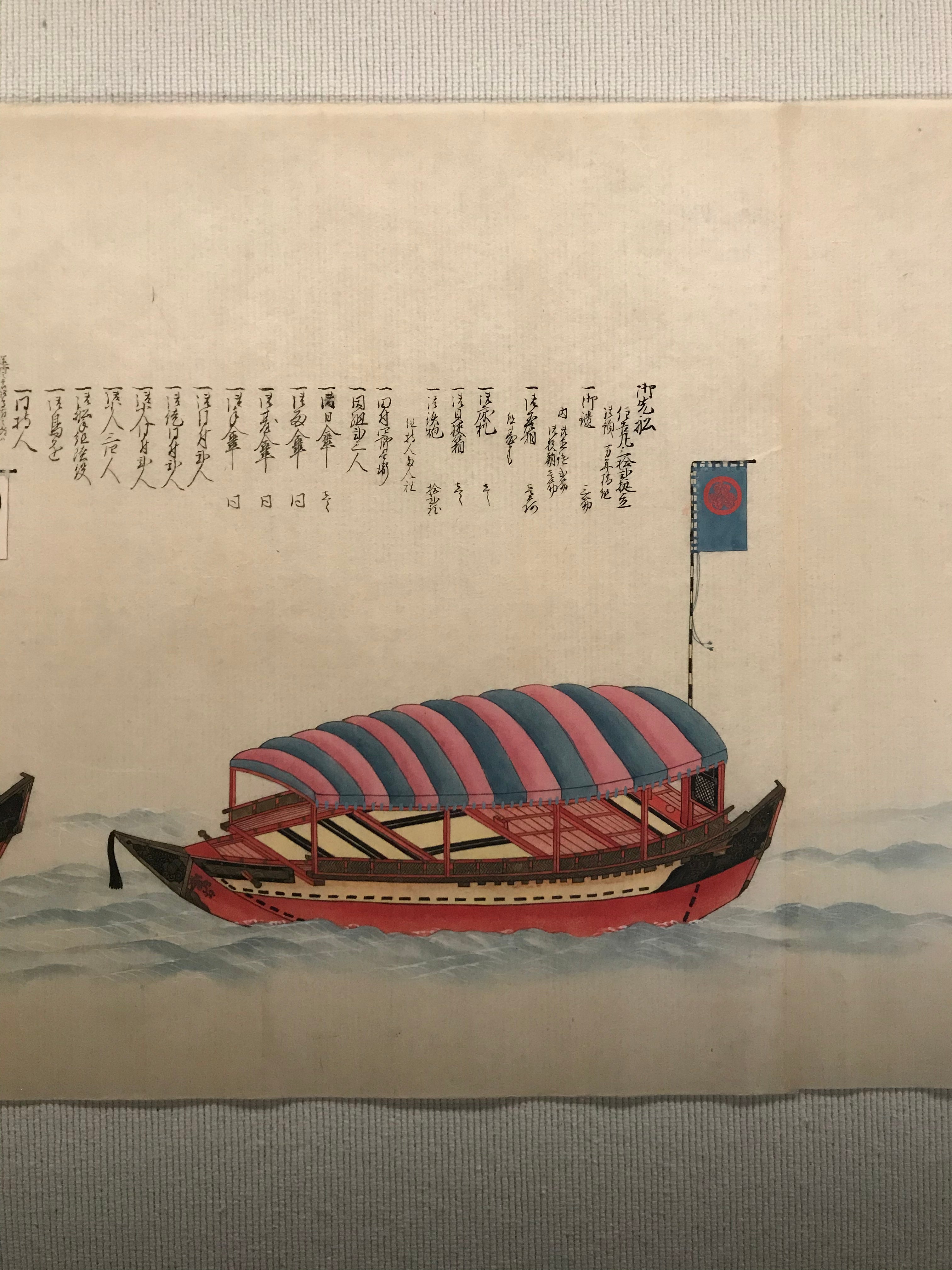

As I grew as a designer, I started to notice that my clothes are both intentionally and unintentionally Japanese. Styles such as my Crescent dress and Haori coat are clearly inspired by the traditional square cut of the kimono cloth I saw everywhere growing up—a shape I take for granted as normal and part of an ancient tradition the most Western designers know nothing about. Since kimonos are always stored in a thin drawer that looks like a flat file, they are folded into a rectangle shape before being wrapped with special paper called Tatoushi and placed in drawers made of a Kiri, a type of wood specifically used for cabinetry. (You see how much one should know about an object before adapting it for personal use and aesthetics!) The producers in my factory are often confused by the build and structure of my clothing. My square, geometric shapes recall the clothing not of the Japan of my youth and the business attire of the average Japanese worker, but the traditional clothing of pre-war Japan before Americans westernized our country. I had become a designer to find a way out of the strict traditions of my upbringing and now those traditions were returning to me in my clothing.

These questions of heritage and tradition were on my mind when I visited Japan recently. As always, on my first day home, I was confused and disoriented. I felt at sea back within the rules and regulations that had dominated my childhood. At a local coffeeshop, which I sought out because it was run by a Black Japanese man and less regimented than other coffeeshops, I was nevertheless flustered by the strict rules governing something as simple as getting coffee. After less than twenty-four hours in Japan, I was immediately reminded of the feeling being an outsider. All the reasons I had left Japan came flooding back at once.

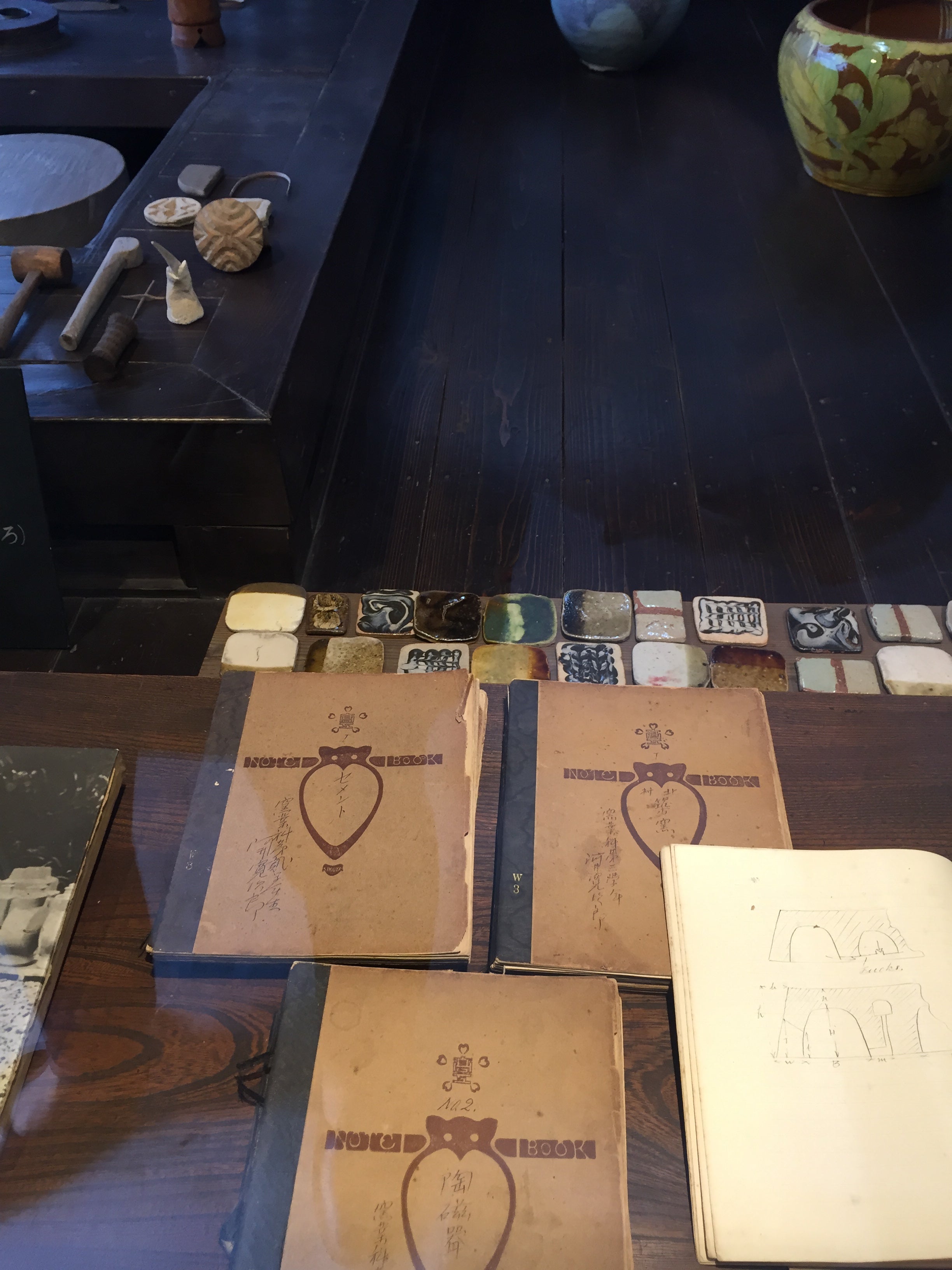

But then something unexpected happened. My mother—the holder of all the cultural traditions in my family—took me to visit a temple in Nara. In my youth, I had grown used to ignoring my mother’s teachings, her endless information about ceremonies and heritage, because I imagined they were irrelevant to the person I wanted to become. But in the Koufuku Temple I began to listen.

I was astounded how much my mother knew about the temple. She knew that a vase that was placed on a top shelf meant that a shogun had taken it from another culture and was baiting the enemy with it, inviting the enemy to spy. She explained that Chigai Dana—a type of geometric shelf—is typical of the Shoin Style of architecture. She knew the meaning of the carving technique called Yosegi Zukuri used by that Unkei when he made enormous wooden sculptures for Buddhist temples. She knew that the pattern on the ceiling was designed in such a way as to put pressure on the enemy by way of psychological intimidation.

As I listened to my mother, I started to understand how and why certain elements of Japanese culture were appearing in my designs. I had always imagined, especially as a Westernized Japanese person—especially as a Japanese person who had fled to the West—that the elements of Japan that were interesting to outsiders and myself were the more Westernized aspects of our culture. But in Nara I started to realize that what is inherent to me and my worldview are not these more obvious conventions, but rather a deeper cultural heritage that reaches back way before the war when Western ideals first broke through and changed Japan forever. What appeals to me are richer traditions of our heritage grounded in the ceremonies my mother insisted upon in my youth. These are what I see in my clothing. These are what I seek out. These are what appear both consciously and subconsciously in my designs—a return to the more ancient customs. And to me, I can now see and appreciate their beauty.

In visiting the temple, I realized, I was taking the first step towards bridging the gap between my Westernized self and my Japanese heritage that is more profoundly engrained in me than I had previously imagined. As are so many things in my development as a designer and a person, this is an ongoing process. I have to acknowledge that I am at the beginning of this journey and still have a lot to learn. I don’t have the language yet to articulate this synthesis beyond how it manifests in my designs. But I’m learning to embrace it and discuss it. It’s an older story—one that goes back before the war to historic styles, customs, and traditions including dress. It’s one that my parents had been teaching be about since I was little, despite the fact that I hadn’t been willing to listen.

But now I am prepared for this return. I am prepared to acknowledge that the way for me to move forward as a designer is actually to take a step back, to keep an eye on the future, while opening myself up to the traditions of the past which I’m now only beginning to learn truly define me, or at least part of me.