Palimpsest

/ˈpaləm(p)ˌsest/

noun

noun: palimpsest; plural noun: palimpsests

a manuscript or piece of writing material on which the original writing has been effaced to make room for later writing but of which traces remain.

In India time and history are layered. On the streets, you can sense the ghost of time that has passed and sense time passing right before your eyes. Buildings and spaces become history but are also part of a continuum. Stories are suggested in the juxtaposition of a dead branch, a broken piece of concrete, a dried chain of marigolds. On a storefront, modern signage coexists with shrines and peeling posters of other people's gods. Which came first? How long will they continue together in this place? What is the story these objects are telling? How did it begin and when will it end?

On the interior of many buildings you can see the shadow left behind by previous inhabitants, the ghost of previous usage, a whole separate context of living in the same place. The paint on the walls has depth—layers of story with colors chipped away so only their edges remain. Painted frames now framing nothing. Whole buildings covered in periwinkle blue at a Maharajah’s request, the color fading and becoming part of another story.

There’s damage of course, the natural evolution of the passage of time—peeling paint, crumbling concrete, chipped wood, dead trees and flowers, faded figures. But the damage is part of the story, part of the continuation, both part of the present and the past. And therefore the damage is part of the beauty.

My overwhelming sense of India was one of texture—of many things coexisting at once, bringing the modern moment into concert with all of those moments that led up to it.

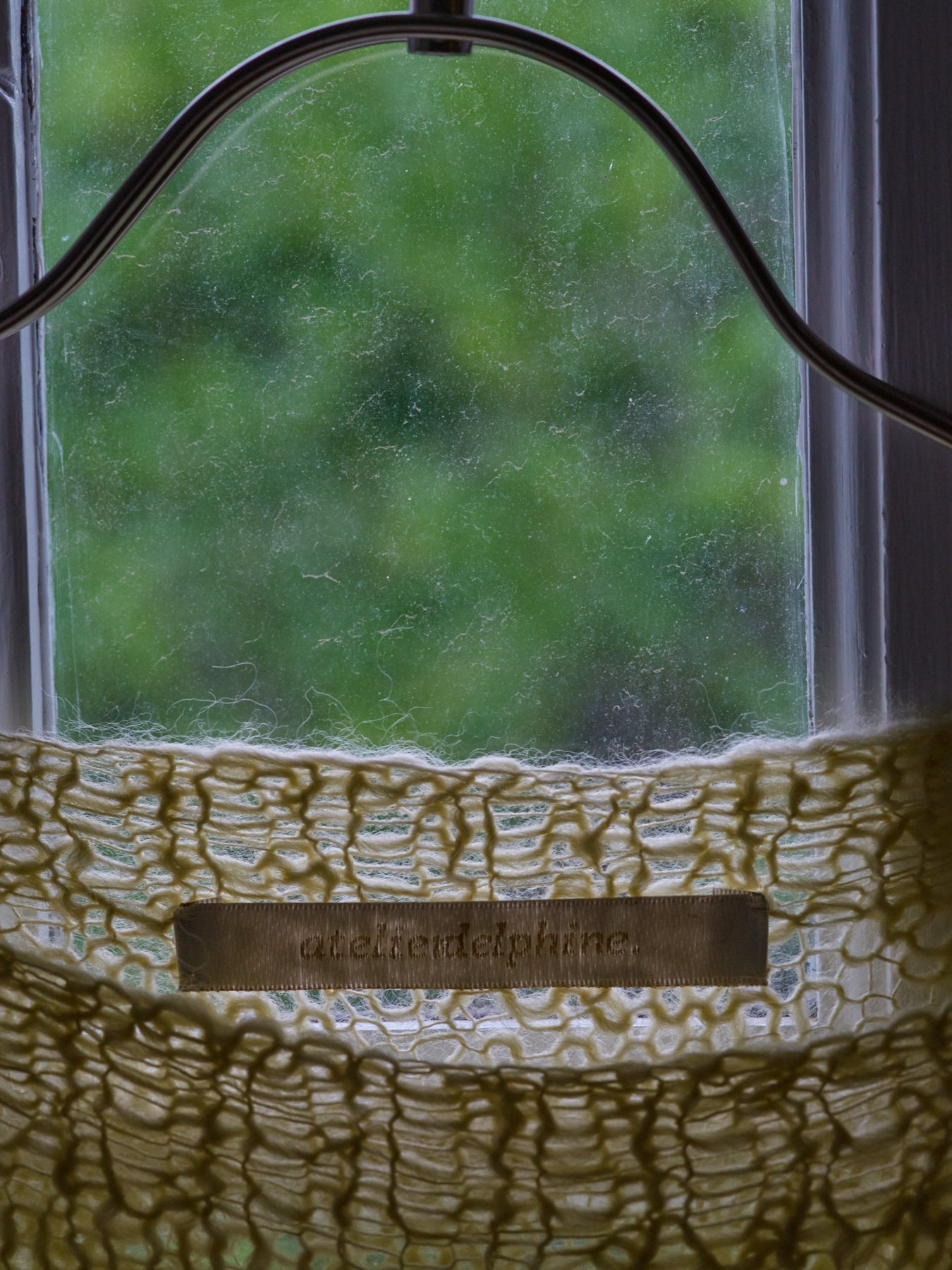

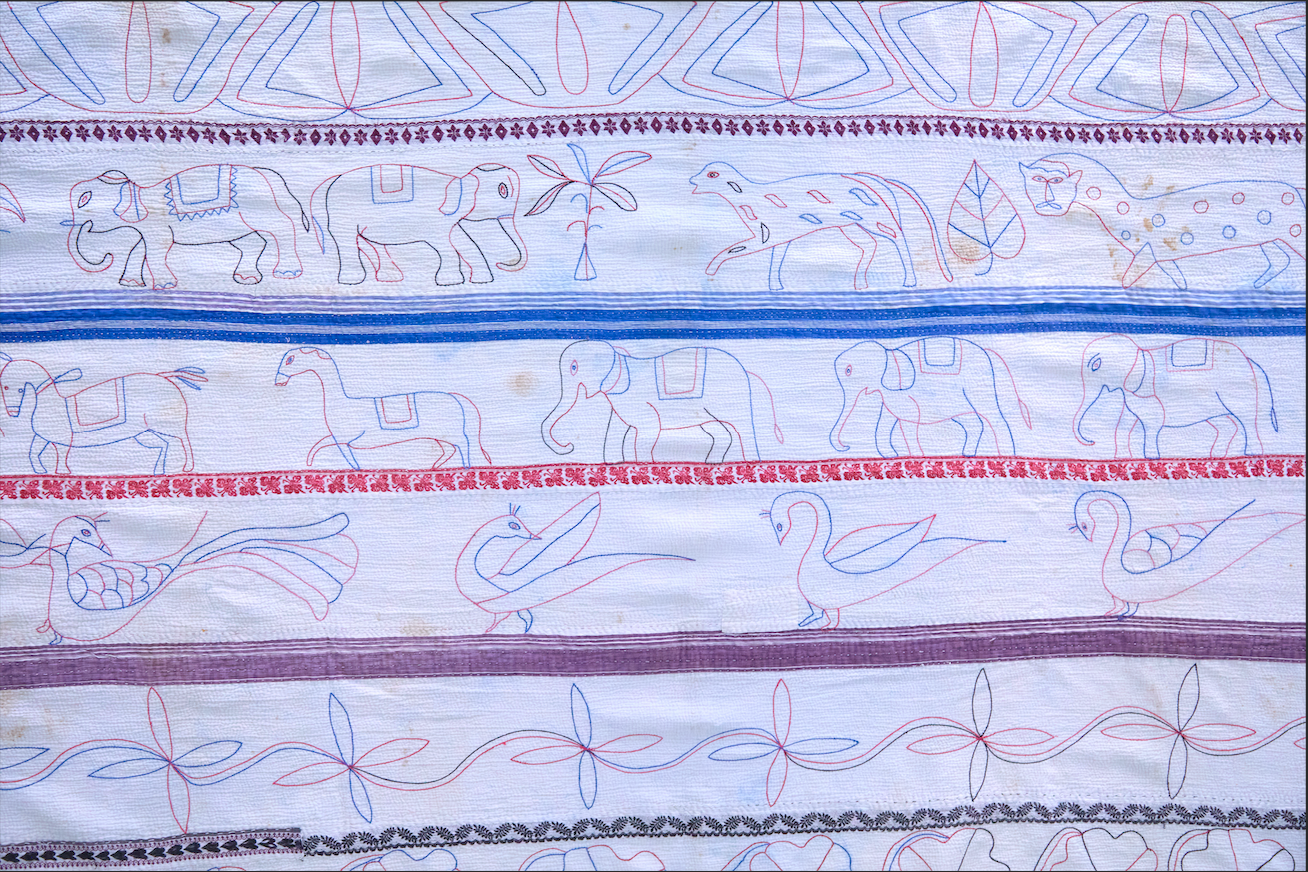

Because I am a fashion designer, I relate to the world through fabric. In Jodhpur, I booked a driver and asked him to take me places that he thought represented not just the tourist side of the city, but more important, his personal and authentic experience of living there. He took me to meet local people—his friends and his wife. We went to several shops where I discovered a wild collection of fabrics, vintage and new. Each one I purchased was a direct link to the store—to the shopkeeper and his or her family, as well as to the moment of discovery—where I found it. I bought fabrics to tell the story of my trip though Jaipur and of Jaipur itself, including one I felt pressured to buy from a high-end shop that caters to elite travels from the US and EU. I chose these fabrics carefully with no notion of repurposing them through my own designs but because each one was an attempt to capture an aspect of the country’s religion, history, and culture.

Back in Los Angeles, a disappointing transformation occurred. Looking at these fabrics when I got them home, I realized they had lost their context, their story. Their handiwork remained beautiful, but suddenly that craftsmanship appeared less important than the missing cultural context of where they were made. Outside of India, these fabrics seemed flat, devoid of religion and history. The people who had made them, their collective consciousness and their heritage, had been lost on the journey across the ocean. In my hands, they had become generically ethnic—not too different from those almost commercialized flea market finds (baskets, beads, embroidered bags and blouses) whose origins are obscured, forgotten, or simply beside the point.

When I considered these vintage pieces in my own home, far from the land where they were made, I longed to access the core, the heartbeat, the nexus of the culture from which I removed them. They were crafted for reasons that I didn’t understand, be they functional, ceremonial, or religious. Their beauty had only increased as they became weathered and worn with use and time. But their stories were missing. All I had was their existence.

This transformation left be both confused and sad. Of course these fabrics were for sale and it was my right to buy them. But as I looked at them, I realized that as a designer I have a responsibility to them that went beyond their purchase. I have a responsibility to their culture and their heritage—to their texture and to stories they tell that brought them into my hands. I understood that owning them wasn’t enough. I needed to go deep within myself and within them to start to understand where they came from so that I could begin to honor their authenticity instead of simply dropping them into my own world.

As I looked at these fabrics in their new home, I allowed myself to wonder what these quilts were going through and how I could continue their story, weave them into my tale, honor their essence and experience. I started to think how could I add to their texture, continue to layer their history, instead of simply assigning them a new beginning.

These fabrics led me to understand that clothes alone cannot tell a story of a culture. They are only one piece of the puzzle—one portal, alongside art, music, religion, food, and history that allows us to understand the core of a people and their heritage. Yet as a designer, I must acknowledge that I hold the key to this single portal and through my own designs I can begin to show people cultural texture that they might have otherwise ignored or

overlooked.

Considering these Indian fabrics back in Los Angeles, I came to see that the meaning and the narrative of a piece goes much deeper than the visible design and that my designs must start from a place in my own core where my own unique worldview is united to my own heritage. And I must, with my work, begin to make that core more accessible to others just as I must begin to acknowledge the foreign core of the culture contained within my Indian blankets

and scarves and suggest to others that they do the same.

My pieces tell a story. So I know that I must choose my words carefully when discussing the quilts, blankets, scarves, and scraps that I brought back from India. They each have their own sceneries, histories, and lineages. And in acknowledging this, I can become more appreciative about how I display them, use them, and describe them. And this appreciation

will both deepen and be reflected in my own work.

What I learned from the pieces I bought in India is that I must continue add to the texture and continue the layering of history that so struck me on my travels. Instead of simply designing, recycling, upcycling, and repurposing, my job is to find an object’s story continue it, honoring it instead of simply using it or reusing it. I must allow the ghost of something’s past to inform its present. Doing this is only this way that I can begin take the first step towards acknowledging the complex core of any culture and come into greater universal understanding of the world and the place of my own work within it.

The connection between an object and its origin is not always clear to me. It’s something I’m continuing to search for every day. And it’s not always easy. I do know, however, that the longer it takes for me to find this connection the more meaningful this connection will be. And not just that—but the longer I work to understand something, the more meaningful this process of understanding becomes. It is the process that it the more essential thing, the never-ending journey, the cycle of learning, understanding, and even becoming. I’m just one piece in the continuation of a story, a small step in its evolution.

It took me a long time to realize that it’s important for me to be vulnerable as a designer, open to the difficulties that come with searching for deeper understanding and admitting that this is an ongoing process. I do not hide this evolution from the public, even though I know that this evolution will at times come with sadness and disappointment, for takes me to places unknown both inside myself in in the world at large, both revelatory and uncomfortable.

This process, that could start with something as simple as a small vintage blanket, doesn’t have to be concluded now. And it shouldn’t be. I am at the start of my journey but I am also aware that, as I set out, it will never end.

(As told to Ivy Pochoda)